In the same year that his landmark memorandum on the Monroe Doctrine was published, on 3 October 1930, J. Reuben Clark was named Ambassador of the United States to Mexico by President Herbert J. Hoover. He held this position until 3 March 1933.

In the same year that his landmark memorandum on the Monroe Doctrine was published, on 3 October 1930, J. Reuben Clark was named Ambassador of the United States to Mexico by President Herbert J. Hoover. He held this position until 3 March 1933.

This was by no means Clark’s first experience with Mexico. In 1906, right after he graduated from Columbia, Clark was appointed Assistant Solicitor of the United States State Department by Elihu Root, Secretary of State in the Theodore Roosevelt administration. This appointment came on the recommendation of the then Solicitor Dr. James Brown Scott who had been Clark’s professor at Columbia. In July, 1910, now in the Howard Taft administration, Clark was appointed Solicitor. When the Mexico Revolution began in 1911, “Clark was called upon to make crucial decisions and recommend courses of action to the secretary of state and President Howard Taft. Of particular concern to Solicitor Clark was the plight of the Saints who lived in Mexican colonies, who were often caught in the middle of the conflict and whose presence in Mexico was resented by the revolutionaries.” [ref]Stephen S. Davis, “J. Reuben Clark, Jr., Statesman and Counselor,” p. 2, retrieved 13 October 2011.[/ref]

Perhaps as a result of the plight of the Mexican Saints, but certainly in response to a global problem, in 1912 Clark published his “Memorandum on the Right to Protect Citizens in Foreign Countries by Landing Forces.”

In 1926, relations between the US and Mexico were strained. President Calvin Coolidge appointed Clark to the General Claims Commission (United States and Mexico). In 1869 the US-Mexico Mixed Claims Commission had been created to consider and adjudge the validity of claims held by citizens of either country against the government of the other, but chiefly had to do with payments owed by Mexico to the Catholic missions, agreed after the Mexico-American War (1846–1848). “The General Claims Commission (Mexico and United States) was constituted under the terms of the General Claims Convention signed Sept. 8, 1923, in Washington D.C. by the United States of America and the United Mexican States. The convention, which took effect on March 1, 1924, was intended to improve relations between the countries by forming a commission to settle claims arising after July 4, 1868, “against one government by nationals of the other for losses or damages suffered by such nationals or their properties” and “for losses or damages originating from acts of officials or others acting for either government and resulting in injustice.” Excluded from the jurisdiction of the General Claims Commission were cases stemming from events related to revolutions or disturbed conditions in Mexico. (The Special Claims Commission was formed to address claims arising from events which occurred between November 20, 1910, and May 31, 1920).”[ref] See http://www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utlac/00024/lac-00024.html retrieved 14 October 2011.[/ref]

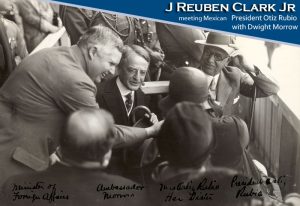

In July 1927, Dwight W. Morrow was appointed Ambassador to Mexico by Calvin Coolidge. Clark and Morrow had served together before, so it was no surprise that Morrow requested that Clark accompany him to Mexico as legal adviser where he dealt with problems arising from the ongoing oil controversy and the agrarian dispute. After ten years of negotiation, Clark was instrumental in forming an agreement that the oil men in the US and Mexico could agree on.

In July 1927, Dwight W. Morrow was appointed Ambassador to Mexico by Calvin Coolidge. Clark and Morrow had served together before, so it was no surprise that Morrow requested that Clark accompany him to Mexico as legal adviser where he dealt with problems arising from the ongoing oil controversy and the agrarian dispute. After ten years of negotiation, Clark was instrumental in forming an agreement that the oil men in the US and Mexico could agree on.

He returned to Washington in 1928 as undersecretary of State to Frank Kellogg (see entry on Clark Memorandum). In the meantime, Dwight Morrow’s ambassadorship in Mexico was coming to an end. Clark was still very much involved with Morrow and the negotiations with the Mexican government on the matter of the Catholic Church’s presence in the country, the ever-present oil controversy, and the agrarian dispute. His last trip to Mexico as undersecretary was in 1929. Morrow had been asked to fill a senate position, and Clark was left in Mexico virtually as the de facto ambassador. This continued until August of 1930 when Clark returned to Utah to be with his family who had left Mexico in May.

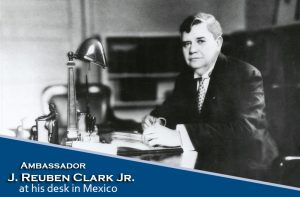

J. Reuben Clark was appointed Ambassador of the United States to Mexico by President Herbert Hoover on 3 October 1931. Of his ambassadorship, Hoover said, “Never have our relations been lifted to such a high point of confidence and cooperation, and there is no more important service in the whole foreign relations of the United States than this.”[ref] Clark Memo 1, 4.[/ref] He was heralded by the editorials as “‘a most obvious power behind the [Morrow] throne’ and predicting him an ‘abler diplomat than Morrow,'”[ref]Frank W. Fox, J. Reuben Clark: The Public Years (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 1980),541.[/ref] But wary of such adulation, before he commenced his ambassadorship, Clark penned these words,

I had been more or less a party to, and more or less responsible for . . . the work of Mr. Morrow in Mexico; I felt that the work was moving along the right lines. I was willing to continue along those lines, thoroughly appreciating that if I succeeded in getting through without trouble it would be credited to Mr Morrow’s work, and that if I failed to get through without trouble it would be charged to inept dumbness on my part.[ref]Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 542.[/ref]

Clark’s first order of business was to confirm the majority of the existing embassy staff, to which he added “especially competent recruits.”[ref]Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 545.[/ref] On 28 November 1930 Ambassador Clark presented his credentials to President Ortiz Rubio at the National Palace. As part of his address, Clark said,

I hope I may be permitted to add a personal word of true friendship for the Mexican people, a friendship I have gained from a considerable residence among them. I have a real sympathy for their struggles and their aspirations, and a deep respect for their lofty ideals and their sterling virtues.[ref]Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 549.[/ref]

The reception at the American Embassy afterward represented a dramatic departure from the Morrow days—Clark served punch and cookies! Prohibition was still in effect in the States, and Clark, of course, as a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, did not drink alcohol. But it was not his religious beliefs that dictated the decision, Clark was representing his country and was not about to flout its laws. The perhaps not too subtle undertone to this declaration was that Clark was departing from the Morrow mission. Having dealt with the main conflicts between the United States and Mexico in the past, Clark “decided that he wanted to move United States-Mexican relations not only beyond specific confrontations but beyond confrontation itself.”[ref]Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 551.[/ref]

Clark’s relationship to the Mexican people as ambassador was characterized as “reserved and yet accessible.” He

spoke to the Press Congress of the World; he delivered the commencement address at the American School in Pachuca; he officially opened the baseball season in Mexico City; he hosted the Boy Scouts of North America; he presented prizes at the country club golf tournament; he guided VIP’s about the capital; he attended to political mail from Washington—and always with a message of peace and understanding between the two neighbors. ‘Our country, right or wrong,’ was a fine maxim for military men, he said to one distinguished gathering—but it had no place among diplomats.[ref]Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 557.[/ref]

Clark had an advantage few if any politicians had the benefit of, a missionary son who was fluent in Spanish (although he served his mission in France). Reuben III was Clark’s seemingly innocent bystander in negotiations, affecting as Fox put it “an expression of bored abstracting that was entirely convincing,”[ref]Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 563.[/ref] while carefully reporting on whatever the translators were either missing or mistranslating.

Following on from the work he did on the Memorandum on the Monroe Doctrine, Clark was ever-more convinced of the need for Mexican sovereignty, but domestic policy stood in its way. The claims commission was still pushing for a new convention, and Clark was embroiled in those negotiations. By the end of his term, he had managed to extend the claims convention for another two years, but Congress did not ratify the extension. At one time, “Senator Henry F. Ashurst of Arizona introduced a resolution in Congress proposing the purchase of nothing less than the whole of northern Mexico.”[ref]Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 564.[/ref] To this and other such sweeping moves, Clark wrote, “That such irresponsibility may sometimes actually shape the relationship of two nations, . . . seems not to be appreciated always by the irresponsibles.”[ref]Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 564.[/ref]

The religious controversy was also an ongoing feature of his ambassadorship, but here too, his approach differed radically from that of his predecessor. Morrow “would settle the religious issue first and talk about diplomatic propriety later; Clark would behave properly first and talk about the church and state later.” [ref]Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 564.[/ref] However, although there was no open warfare as had been during the days of the Cristeros War, the deterioration of the relationship between the Catholic Church and the state almost ignited at the four hundredth anniversary of the appearance of the Virgin of Guadalupe when the rumor went round that the government was going to hijack the Virgin’s sacred shawl. Clark was called in to meet with General Plutarco Calles, the former president, now self-styled Jefe Máximo (who was not then on speaking terms with his supposed puppet, President Rubio). Clark’s response to the crisis was skillful:

I stated that whether or not this mantle was removed from the Cathedral to the Museum was none of my business and none of my Government’s business—I appreciated that; nevertheless, I wished to point out to him that if this were moved and there was a riot and a great many people killed, that it would present a problem because of the trouble which the Catholics in the United States would make, declaring that the situation was out of hand and of course asking for intervention. I said that was my sole interest in the matter and I presented that merely for his consideration.[ref]Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 575.[/ref]

The matter was resolved.

General Calles was to be instrumental in one of Clark’s triumphs during his ambassadorship. One of the disputes Clark had inherited had to do with the Rio Grande. Known as the Chamizal controversy, this was a 600-acre border dispute between the US and Mexico based on an 1852 survey of the bed of the river and its current channel. The boundary negotiations had see-sawed throughout his ambassadorship and were looking promising with the appointment of the former Mexican ambassador to the United States, Manuel Tellez, as foreign secretary, but a new Mexican cabinet, created with the unwilling departure of President Rubio, forced Tellez out and threatened to stall the agreement as it was about to be ratified. Clark again met with Calles, this time with new president Abelardo Rodriguez and the new foreign minister J. M Puig Casauranc. Calles suggested concentrating on a settlement based on the river rectification alone, without the Chamizal controversy. “By February 1, 1933, Ambassador Clark and Foreign Minister Puig Casauranc were able to sign a convention providing for the rectification of the river and the stabilization of the international boundary. . . . The troublesome issue of the Chamizal would remain unresolved for the next thirty years, but the Rio Grande itself was subdued.”[ref]Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 578.[/ref]

Clark was now 62; the Republicans had lost the election, and he was about to be recalled. In February 1933 Puig Casauranc hosted a dinner and reception in the ambassador’s honor. An excerpt from Clark’s address at this time serves to summarize the impact of his ambassadorship.

History records a patient, indomitable racial will to hold the heritage of this past, a heritage of culture, of character, of experience, and of wisdom, which is a graven record upon the mind and heart of those remnants of former peoples that make the present race. It has seemed to me, Mr. Minister, that all this past is an integral and vital part of the present, and that, therefore, to understand the present we must comprehend something at least of the past. It is in this view and in this spirit that I have approached my work in Mexico; and this view and this spirit have given me a tolerance for the ardent zeal with which at times the race has surged to and fro; they have given me a sympathy with the aspirations and ideals proclaimed in your revolution; they have accounted, and have given excuse, if not reason, for the measures which always mark a rebellion, when a people, downtrodden for generations, grope upwards for the light of the sun. This view and this spirit have given me the faith that, coming down through the generations, there lies somewhere in the deep recesses of the racial mind of Mexico, a spark of that cumulated wisdom and experience, descended from former ages and greatness, that shall in due time blaze forth and light the race along a new path, leading to greater glories.[ref]”Fox, J. Reuben Clark, 582.[/ref]