As a frontier farm boy and member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (sometimes erroneously called the “Mormon Church”) J. Reuben Clark enjoyed what might be considered a perfect childhood for the building of a man of character. He was the first of ten children born to Joshua R. and Mary Louisa Wooley Clark, and as a frontier farm boy and the eldest child, shouldered a great deal of responsibility.

As a frontier farm boy and member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (sometimes erroneously called the “Mormon Church”) J. Reuben Clark enjoyed what might be considered a perfect childhood for the building of a man of character. He was the first of ten children born to Joshua R. and Mary Louisa Wooley Clark, and as a frontier farm boy and the eldest child, shouldered a great deal of responsibility.

J Reuben Clark, Jr.’s Parentage

Reuben’s father, Joshua, served with the Union forces during the Civil War. During the war, he organized debates and public speaking, so the soldiers would use their down-time constructively. After the war and odd jobs in Utah, Minnesota, and Montana, in February 1867, Joshua and a friend started a difficult trek from Montana to Utah. They arrived in Farmington (north of Salt Lake City) in March and attended their first Mormon meeting. Joshua Clark, Sr. was impressed with the doctrines of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and said the Mormons had been grossly misrepresented. Both he and J.C. Hancock were baptized after hearing Prophet Brigham Young speak in a Mormon general conference of the LDS Church. Joshua Clark was talented in working with his hands, and many of his wage-earning jobs entailed physical labor (he had worked his way west through Utah as a trapper and freighter). But he was also well-read, and cultured. He was hired to teach school in Grantsville, Tooele County, Utah. Joshua married Mary Louisa Woolley, whose parents were among the Mormon pioneers who crossed the plains to Utah in 1848. She was born on the way.

In 1882, Joshua wrote of his children: “May God spare their lives (7 sons, 3 daughters)…and may they grow up to man and womanhood and become bright stars in the great latter-day work is the prayer and heartfelt desire of their parents.”

J. Reuben Clark’s Boyhood

J. Reuben Clark, Jr.’s childhood tethered him to work. By age nine he was milking cows; by age eleven he was branding calves and herding cattle; by age thirteen he was plowing the fields; by age fifteen he was driving cattle alone in the mountains for days on end. He was said to be skilled at riding, training, and handling horses. He could train them and shoe them. Of necessity, he also sheared sheep; harvested crops; pitched hay; managed irrigation; hauled and spread manure; hand-cut, hauled, and stacked corn and cane stalks; bound wheat and picked fruit. He hauled farm produce, willows and posts for fences, water, rock, and firewood from the mountains— sometimes in freezing weather. He hauled salt from Kimball Island in the Great Salt Lake. At least once in his career, he said his first, middle, and last names were “work.” [1]

Grantsville is located thirty-three miles southwest of Salt Lake City in Tooele Valley, and at the time, it was a four-hour trip by buggy and train from Grantsville to Salt Lake. Large tracts of desert land provided winter grazing for cattle in the winter. South Mountain to the south, and the Stansbury Range to the west, provided timber, water, berries, and summer grazing. The Latter-day Saints who settled the area were faithful, industrious, and community-oriented. Although hard work was mandatory for survival, the year was often punctuated by community events, parties, dances, celebrations, plays, lectures, and outdoor recreation. Clark participated in mounting dramatic productions from his youth, and acted in some. He manifested a gift for public speaking, comedy, and humor at a young age. Clark also enjoyed the childhood fun available on the frontier — sledding in the winter and swimming in the summer.

Grantsville is located thirty-three miles southwest of Salt Lake City in Tooele Valley, and at the time, it was a four-hour trip by buggy and train from Grantsville to Salt Lake. Large tracts of desert land provided winter grazing for cattle in the winter. South Mountain to the south, and the Stansbury Range to the west, provided timber, water, berries, and summer grazing. The Latter-day Saints who settled the area were faithful, industrious, and community-oriented. Although hard work was mandatory for survival, the year was often punctuated by community events, parties, dances, celebrations, plays, lectures, and outdoor recreation. Clark participated in mounting dramatic productions from his youth, and acted in some. He manifested a gift for public speaking, comedy, and humor at a young age. Clark also enjoyed the childhood fun available on the frontier — sledding in the winter and swimming in the summer.

The Clark family was unabashedly loving. After a hard day’s work, Reuben’s father, Joshua Clark, enjoyed nothing better than playing and rough-housing with his children. Birthday and holiday celebrations were modest, due to the family’s tight finances, but rich with sincere affection. The family was also devoutly religious. J. Reuben Clark Jr.’s grandfather had been a minister in the Dunker Faith (Church of the Brethren).

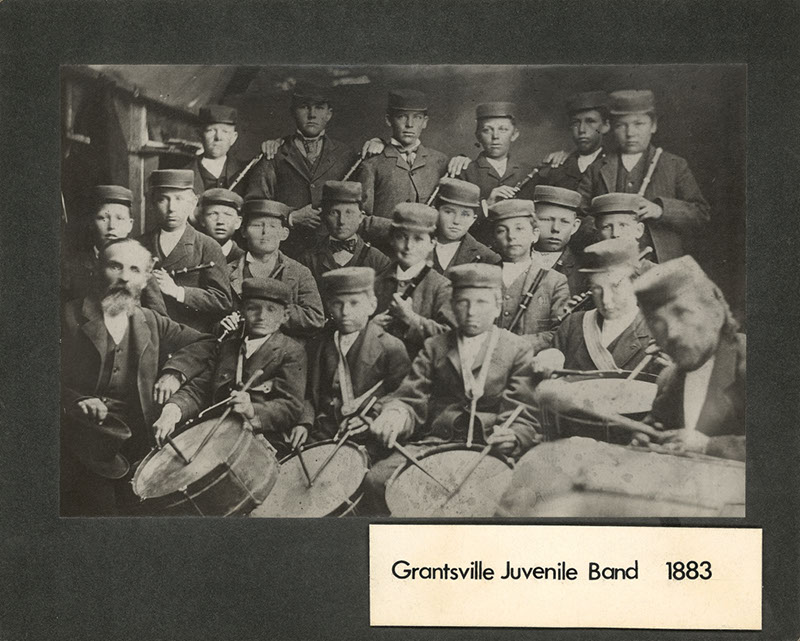

Education and culture were important in the Mormon communities in Utah Territory and later the State of Utah. Joshua Clark, Sr. was the sort of man who, while doing business in Salt Lake, would sleep in a hay loft in order to afford to see a Shakespearean play, and would make great sacrifices to afford to buy a good book. The small library in the Clark home was made up of history books, classics, and an encyclopedia, plus the religious works of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Although young Reuben’s education was spotty in his youth, due to the demands of farm life and meager family resources, he was able to take music lessons and to play with various bands. He played the piccolo and then the flute.

Education and culture were important in the Mormon communities in Utah Territory and later the State of Utah. Joshua Clark, Sr. was the sort of man who, while doing business in Salt Lake, would sleep in a hay loft in order to afford to see a Shakespearean play, and would make great sacrifices to afford to buy a good book. The small library in the Clark home was made up of history books, classics, and an encyclopedia, plus the religious works of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Although young Reuben’s education was spotty in his youth, due to the demands of farm life and meager family resources, he was able to take music lessons and to play with various bands. He played the piccolo and then the flute.

Joshua Clark, Reuben’s father, became the clerk and then the superintendent of the Grantsville educational co-op. In 1878 he was elected the Tooele County Superintendent of Schools. He was also president of the Tooele County Education Association. When he later taught at a local private school, Reuben was able to be formally educated for the first time. He was ten years old, and in the past had been schooled by his mother. Reuben was not at school every term. Sometimes, financial difficulties and farm work kept him at home. His father once related that Reuben would “rather miss his meals than to miss a day from school.” [2] After completing the eighth grade, the highest grade offered at the Grantsville school, Reuben repeated it two more times.

By 1879, Joshua was also an assessor and tax collector, and his two eldest sons helped with the accounting and record-keeping. Because his father was so busy, Reuben picked up more responsibility for the farm work. But an opportunity presented itself for Reuben to continue his education, and for that, he would need to relocate to Salt Lake City.

J. Reuben Clark’s Education

The Church established the beginnings of its school system under Karl G Maeser. In 1890, at age 19, Reuben began to study at Latter-day Saints College, which opened in 1886. Reuben had a deep thirst for learning and was always reading. The college was renamed The Central Normal College of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It was located in the Social Hall on State Street south of the Salt Lake Mormon Temple. Reuben lived at the home of his Aunt Rachel Simmons (his mother’s sister) while he studied. He achieved extremely high grades.

In January 1891 James E. Talmage, the principal, offered Reuben the position of assistant curator of the Deseret Museum. This was a paid position, but it meant some time off from school. The income would be a great help for a family with very little money, and the position was offered also In place of serving a full-time mission for the Mormon Church. Reuben, after counseling with his parents, accepted. The museum’s contents had been moved and were in disarray, as were its records. Reuben organized all the displays and artifacts and added Dr. Talmage’s personal mineral and fossil collection. Meanwhile, Reuben studied on his own and attended lectures and debates. His family often visited him in Salt Lake City, and he went to Grantsville for holidays. Reuben learned to type in 1892, when typing was considered a woman’s occupation.

James E. Talmage was released as principal to prepare to create a new college for Church. Reuben would attend for four years and help Talmage in as an assistant in the chemistry lab for pay, and still stay on at the museum. Talmage was the greatest LDS scholar-scientist of that generation, and his patronage was very meaningful for J. Reuben Clark. Talmage encouraged him later to study in the East and called him “the greatest mind ever to leave Utah.”

In 1893 Reuben’s younger brother, Elmer, died at age 16 of an abdominal abscess, a devastating event for the family. Reuben entered the University of Utah in 1894. These were extremely difficult times in Utah. The Edmunds-Tucker Acts and the Morrill Act were designed by the U.S. Government to break the Mormon Church as an institution. Church property was confiscated by the government, and some private individuals were enriching themselves at the expense of the Church.

The buildings on Temple Square and other church offices were placed in receivership and then rented back to the Church. In an attempt to stop the flow of European converts, the government dissolved the Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company, the chief agency for immigration. More and more Saints were stripped of their voting rights. Schools were placed under the direction of the federally appointed territorial Supreme Court. U.S. marshals arrested more men who were then nearly automatically sentenced to prison. The LDS Church had to cut back radically on its educational investments. The Church instead supported the University of Utah, founded in 1850, the first university west of the Mississippi.

James E. Talmage became president of the U of U, and also the first recipient of the recently endowed Deseret Professorship of Geology. Again, Reuben served as his personal assistant. Reuben’s father was called to the Northern States Mission of the LDS Church in 1894, and four months later was made president of the mission. Reuben was working for meager wages, but still managed to send money to support his father during his mission for the Church. In those days, married men with children were called to serve missions, and some missions lasted for years. Joshua was released in June 1896 due to his wife’s illness.

James E. Talmage became president of the U of U, and also the first recipient of the recently endowed Deseret Professorship of Geology. Again, Reuben served as his personal assistant. Reuben’s father was called to the Northern States Mission of the LDS Church in 1894, and four months later was made president of the mission. Reuben was working for meager wages, but still managed to send money to support his father during his mission for the Church. In those days, married men with children were called to serve missions, and some missions lasted for years. Joshua was released in June 1896 due to his wife’s illness.

Reuben finished six years of college work (including high school preparatory, because he hadn’t graduated from high school) in four years. He was clerk in the president’s office at the University of Utah, and was listed as faculty in the directory. He also continued his ongoing work at the museum. During his last year of college, Reuben was the editor of The University Chronicle, also a contributor. He was valedictorian of his graduating class, and his speech is still in print.

See also: The Legacy of J. Reuben Clark.

[1] Yarn, David H. Jr., Young Reuben: The Early Life of J. Reuben Clark, Jr. 1979, Brigham Young University Press, Provo, Utah, p. 15.

[2] Clark, Joshua R., Sr., personal journal, edited by David H. Yarn, Jr.